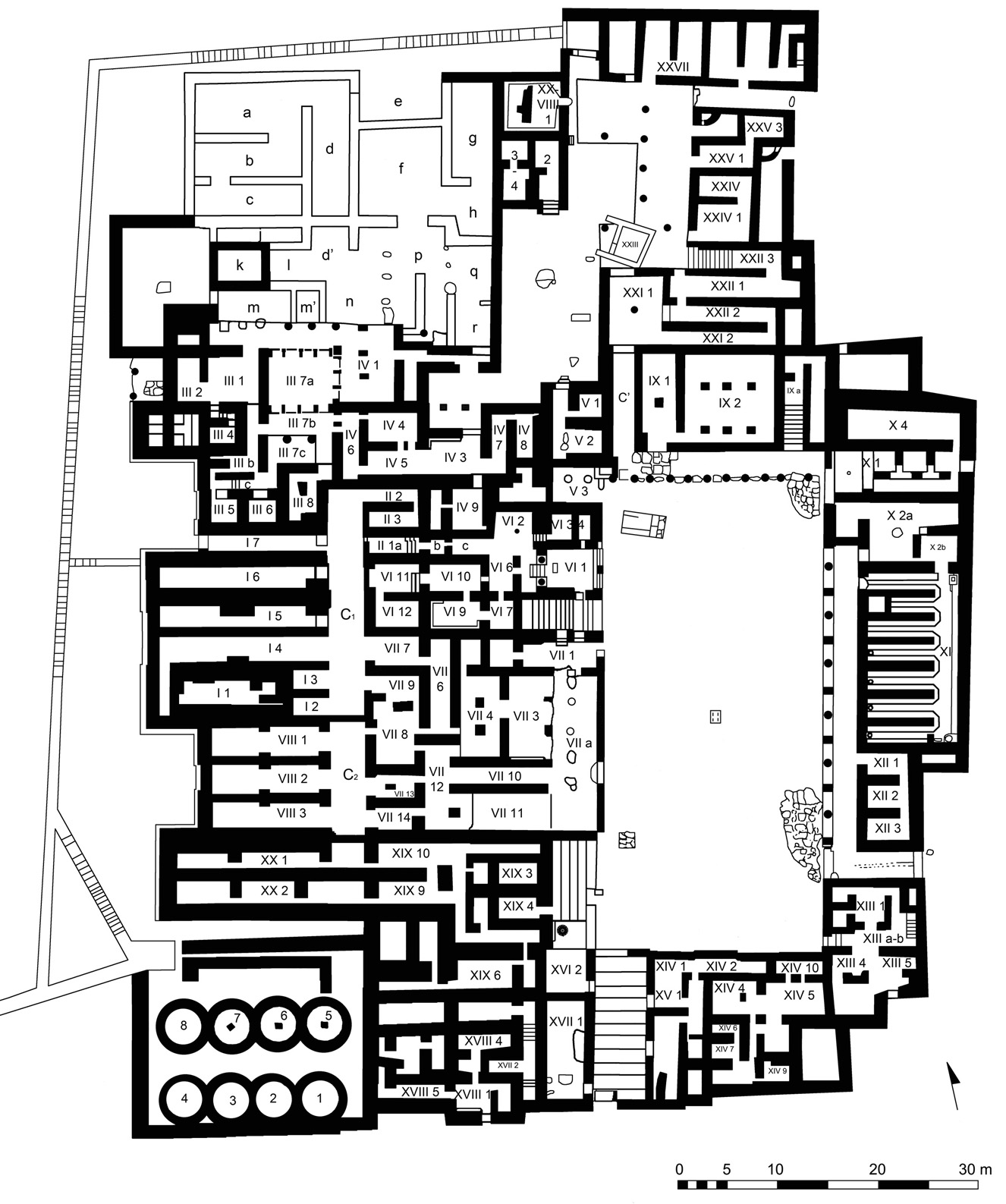

The Palace of Malia was discovered in 1915 by the Ephor of Ancient Monuments of Crete, Joseph Hazzidakis, who began to explore the edifice in 1919. The French School at Athens joined the project from 1922 onwards, after the successful exploration of the Chrysolakkos Building in 1921, which included the discovery of the celebrated honeybees pendant. The Palace was excavated in its entirety during the large-scale excavations that followed until 1936, under the direction of Fernand Chapouthier, assisted notably by Jean Charbonneaux, Pierre Demargne, André Dessenne and René Joly (fig. 1, 2 and 3). Work to consolidate and study the Palace, accompanied by several surveys, subsequently took place but it was not until 1964 that Oliver Pelon initiated the systematic exploration of the lower levels of the edifice. His investigations brought to light the remains of a protopalatial state (1900-1700 BC) in several places in the Palace, as well as signs of a prepalatial occupation under rooms IX 1-2, in the ‘bunker’ I 1 and under the Central Courtyard of the edifice (fig. 3). These suggest that an open space may have existed on the site of the Palace from Early Minoan IIB (2450-2200 BC), although the construction of a coherent set of structures around this open space — a ‘Palace’ in the proper sense of the term — only dates from the beginning of the second millenium.

Figure 1. Photograph of a worker in action during the excavations of the Palace of Malia (date unknown) © FSA

As well as a detailed description of the architectural remains and several articles examining a range of subjects relating to the Cretan palatial system in particular, Olivier Pelon also published numerous reports and articles communicating the results of his surveys at the Palace. After his unexpected death in 2012 and the premature death of his collaborator Veit Stürmer in 2013, numerous questions remain. Probably the most debated is that of the date of the Palace’s construction. On the basis of the discovery of a foundation yard containing ceramics dating from Early Minoan III / Middle Minoan IA, Olivier Pelon suggested that the Palace of Malia was constructed from the Middle Minoan IA (2050-1900 BC), i.e. before the Palaces of Knossos and Phaistos, built in Middle Minoan IB (1900-1800 BC). The ‘First Palace’ or the protopalatial Place of Malia was destroyed at the end of Middle Minoan IIB, around 1900 BC, by a cause that is still unknown. It is not known whether the edifice was reconstructed immediately after this destruction, since the remains dating from the Middle Minoan III phase (1900-1600 BC) are not very abundant, but it is certain that during the Middle Minoan III / Recent Minoan IA transition, a ‘Second Palace’ was built and subsequently used until its eventual destruction in Recent Minoan IA (1600-1510 BC) or in Recent Minoan IB (1510-1430 BC).

Figure 2. Aerial View of the Palace of Malia, seen from the North-West. Photograph G. Cantoro (IMS-FORTH) © FSA

If the broad brushstrokes of the building’s history are known to us, many questions remain regarding the architectural and stratigraphical development of the Palace of Malia. A new project for the study of the Palace, with a view to publication, was begun in 2014 under the direction of Maud Devolder and aimed to address precisely these questions. Beyond the date of the construction of the building, the aim is to examine: the sequence of architectural development and the phases of protopalatial occupation of the edifice until its destruction in Middle Minoan IIB; the sequence of architectural development and the phases of neopalatial occupation of the edifice, until its destruction in a late phase of the Recent Minoan IA, or even of Recent Minoan IB; and its reoccupation in later phases. For each of the major periods of Minoan history, the goal is to establish the state and functions of the edifice. This objective forms part of more general research questions, i.e. concerning the origin of the Minoan palaces, their architectural development, their internal functioning and how they operated with respect to their place in each establishment (how did they complement the activities practiced in the city and in the peri-urban space?), and also their role in the political, economic, and social organization of the island. The new project plans to examine these questions by offering a synthesis of investigations already conducted on the edifice while also providing a new perspective of the latter. The project is based on a new architectural study of the ruins and of material conserved in the storage rooms of the French School of Athens in addition to the Ephoria of ancient Greek monuments in Malia. This will enable us to tie together data from previous excavations and surveys conducted by Olivier Pelon with a new study of the ruins and the material found there.

Figure 3. Plan of the palace of Malia (final phase), based on plans drawn up by E. Andersen (Pelon 1980, plan 28) and M. Schmid and N. Rigopoulous (Pelon 2002, pl. XXXII). The rooms (in Arabic numerals) are preceded by the number of the Sector to which they belong (in Roman figures). © FSA

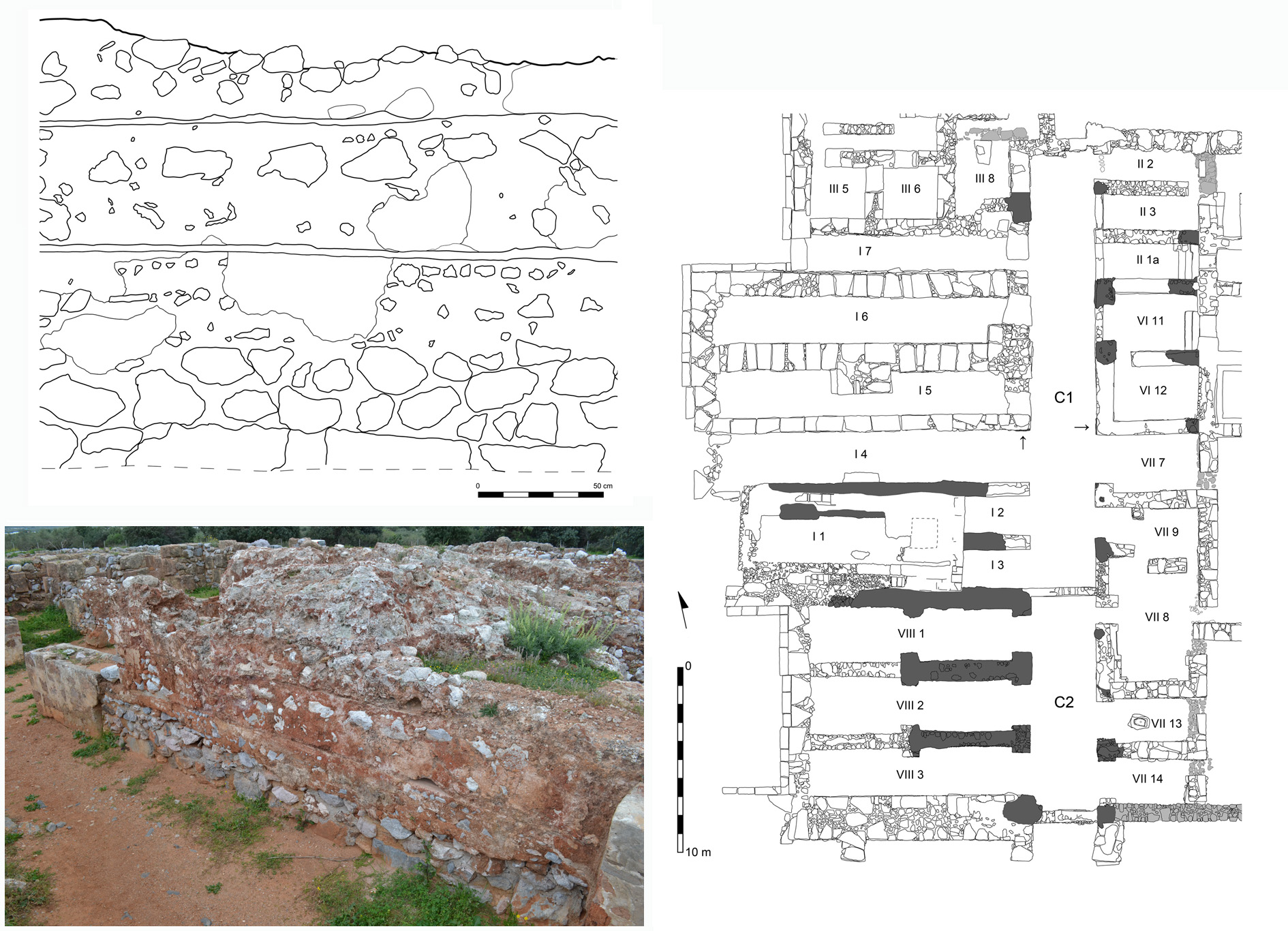

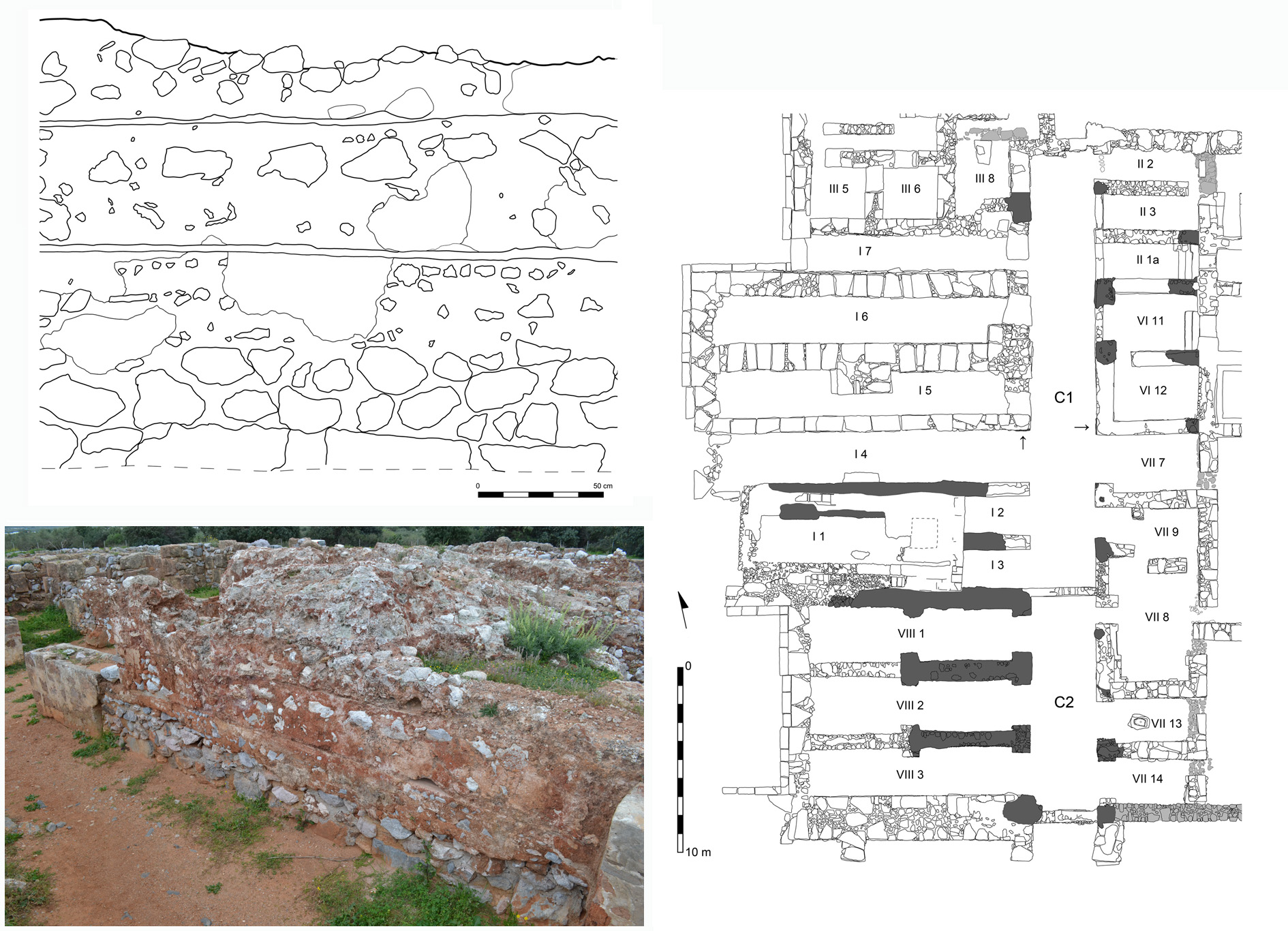

Architectural study of the ruin has already allowed us to reveal how the neopalatial edifice integrated the remains of the protopalatial Palace. Observation of the walls of the West Storehouses has in this regard indicated the presence of protopalatial walls constructed on interlocking layers placed on top of each other. These layers are composed of layers mixing rubble with large quantities of earth, each of which seems to have been pressed down using a wooden device before the next layer was added. These walls, of which only some vestiges remain, are linked to a floor composed of protopalatial plaster and are incorporated into the neopalatial edifice (fig. 4). Their preservation is sometimes limited to a head of a wall obscured by modern restorations, but they attest to the existence in the western wing of the protopalatial Palace of a series of narrow, parallel rooms which, it is suggested, served to store staple provisions.

Work is thus continuing to restore the different states of the Palace of Mali. This work will put into perspective material from older and more recent excavations, providing a picture of the historic function or functions of this edifice. This project, under the aegis of the French School of Athens, also benefits from the support and collaboration of the Humboldt Foundation, the Gerda Henkel Foundation, UCLouvain, the INSTAP, the Onassis Foundation and the IMS-FORTH.

Figure 4. Layout and image of a protopalatial wall in layers of stacked rubble (left) and a plan of the Palace’s ‘Western Storerooms’ with the location of the aforementioned walls in dark grey (right) (M. Devolder and K. Papachrysanthou) ©FSA

To the west, the narrow rooms formed using these palatial walls — probably storerooms — are bordered by a facade with a euthynteria composed of blocks of grey-black and sandstone grey crystalline limestone that were reused in a number of different ways (column bases, doorsteps or lintels) in the neopalatial Palace (fig. 5). The precise form of the walls constructed on this euthynteria is not yet known, but it should be remembered that the facades of the protopalatial Palaces of Knossos and Phaistos are also built on a limestone euthynteria and that there these facades are constructed on top of blocks of orthostates. The restoration in the western wing of the Palace of Malia of storerooms composed of narrow rooms and bordered by a levelling foundation in limestone thus seems to reinforce the idea of an ‘architectural community’ of Minoan Palaces in the Protopalatial period.

Figure 5.

Figure 5. Image and outline of blocks of black-grey and sandstone grey crystalline limestone from the limestone euthynteria of the western protopalatial facade of the Palace of Malia and reused in a number of ways in the neopalatial edifice (K. Papachrysanthou and M. Devolder) © FSA

Work is thus continuing to restore the different states of the Palace of Mali. This work will put into perspective material from older and more recent excavations, providing a picture of the historic function or functions of this edifice. This project, under the aegis of the French School of Athens, also benefits from the support and collaboration of the Humboldt Foundation, the Gerda Henkel Foundation, UCLouvain, the INSTAP, the Onassis Foundation and the IMS-FORTH.

Bibliographical references

- M. Devolder, forthcoming in 2017. « L’assise de nivellement en calcaire de la façade Ouest protopalatiale du Palais de Malia », Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 141.1.

- M. Devolder, forthcoming in 2017. « Architectural Energetics and Late Bronze Age Cretan Architecture. Measuring the Scale of Minoan Building Projects », in Letesson Q. et C. Knappett, Minoan Architecture and Urbanism. New Perspectives on an Ancient Built Environment.

- M. Devolder, 2016. «The Protopalatial State of the Western Magazines of the Palace at Malia (Crete) », Oxford Journal of Archaeology 35.2, p. 141-159.

- M. Devolder, forthcoming. « Travaux de l’École française d’Athènes en 2014-2015. Malia. Le Palais », Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 139-140.2.

- M. Devolder, 2014. « Travaux de l’École française d’Athènes en 2013. Malia. Le Palais », Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 138.2, p. 781-784.

General References for Research on the Palace of Malia

- F. Chapouthier and J. Charbonneaux, 1928. Fouilles exécutées à Mallia. Premier rapport (1922-1924) (Études Crétoises, I).

- F. Chapouthier and R. Joly, 1936. Fouilles exécutées à Mallia. Deuxième rapport : exploration du palais (1925-1926) (Études Crétoises, IV).

- F. Chapouthier and P. Demargne, 1942. Fouilles exécutées à Mallia. Troisième rapport : exploration du palais, bordures orientale et septentrionale (1927, 1928, 1931 et 1932) (Études Crétoises, VI).

- F. Chapouthier, P. Demargne and A. Dessenne, 1962. Fouilles exécutées à Mallia. Quatrième rapport : exploration du palais. Bordure méridionale et recherches complémentaires (1929-1935 et 1946-1960) (Études Crétoises, XII).

- O. Pelon, 1980. Le palais de Malia. V (Études Crétoises, XXV).

- O. Pelon, 1982. « L’épée à l’acrobate et la chronologie maliote (I) », Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 106, p. 165-190.

- O. Pelon, 1983. « L’épée à l’acrobate et la chronologie maliote (II) », Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 107, p. 679-703.

- O. Pelon, 1993. « La salle à piliers du palais de Malia et ses antécédents : recherches complémentaires », Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 117, p. 523-546.

- O. Pelon, 2002. « Contribution du palais de Malia à l’étude et à l’interprétation des ‘palais’ minoens », in J. Driessen, I. Schoep et R. Laffineur (éd.), Monuments of Minos. Rethinking the Minoan Palaces. Proceedings of the International Workshop “Crete of the hundred Palaces?” held at the Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, 14-15 December 2001 (Aegaeum, 23), p. 111-121.

- O. Pelon, 2005. « Les deux destructions du palais de Malia », dans I. Bradfer-Burdet, B. Detournay and R. Laffineur (éd.), Kris Technitis. L'Artisan crétois : Recueil d'articles en l'honneur de Jean-Claude Poursat, publié à l'occasion des 40 ans de la découverte du Quartier Mu (Aegaeum, 26), p. 185-197.

- O. Pelon et M. Hue, 1992. « La salle à piliers du palais de Malia et ses antécédents », Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 116, p. 1-36.

- J. W. Shaw, 2015. Elite Minoan Architecture: Its Development at Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia.

© FSA. M. Devolder